The Huntsman's Eye: At The Portland Museum of Art

I voraciously gather images to use for reference in my artwork. I especially like to collect photographs of artworks that move me in some way. I spend hours in the studio looking at these images of paintings and sculptures and then jotting down my thoughts and ideas.

A year ago, on my birthday, I was traveling in Maine and shot a few photos along the way. Modern Kicks' entry on the Neil Welliver exhibition, currently at the Portland Museum, brought back memories of that journey. On that gray day in Portland, two works in the collection stood out.

Winslow Homer (1836-1910)

Winslow Homer (1836-1910)

Sharpshooter, 1863

oil on canvas

12 1/4 x 16 1/2"

Portland Museum of Art, Maine

USMC Sniper Team, 2004

USMC Sniper Team, 2004

Photo by: Gunnery Sgt. Keith A. Milks

Winslow Homer's "Sharpshooter" is as relevant as the front page of today's New York Times.*

Alexander Eliot in "Three Hundred Years of American Painting" describes how Winslow Homer's "huntsman eyes saw the world his contemporaries saw, only much more sharply." For Alexander Eliot, Homer's paintings are "products of intense and reverant looking, carried on for, not for hours or days, but for years."

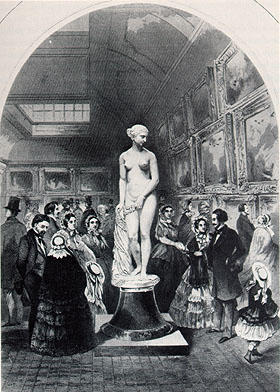

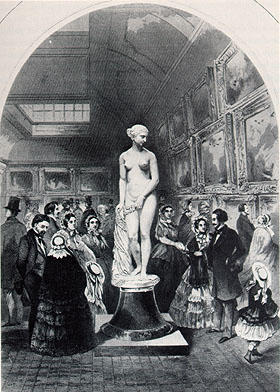

Hiram Powers (1805-1873)

Hiram Powers (1805-1873)

Bust of "The Greek Slave", after 1845

marble

24 1/4"

Portland Museum of Art, Maine

Hiram Powers artwork,"The Greek Slave", was arguably the most famous contemporary sculpture in mid-nineteenth century America. The bust in the Portland Museum is derived from the full figure sculpture that toured the United States.

Over one hundred thousand people paid to see "The Greek Slave" during its 1847-1848 tour.

Over one hundred thousand people paid to see "The Greek Slave" during its 1847-1848 tour.

Robert Hughes in "American Visions" explains that an American artist could approach the concept of the Ideal "if he lived in Italy, and between 1830 and 1875 about two hundred of them did. Notable among them were the 'American Florentines,' led by a former machinist from Cincinnati, the sculptor Hiram Powers."

Hughes goes on to explain that Power's "Greek Slave" was a modern retelling of the Uffizi's "Medici Venus" with chains added as a cache-sexe: "This, Americans thought was the first truly moral nude they had ever seen."

What I enjoy most about the Portland Museum's bust of the "Greek Slave" is the absence of chains and the anecdotal context that shrouded Power's full scale version. We can look upon this work as a sculpture of a real, though idealized, woman. As viewers, we are not told what to feel nor does her nakedness seem unwilling. Without bound wrists, the overt moral clothing that covered her is absent. The figure is more ambiguous and more modern.

* (As I write this the 2,000th US death in Iraq has been announced)

A year ago, on my birthday, I was traveling in Maine and shot a few photos along the way. Modern Kicks' entry on the Neil Welliver exhibition, currently at the Portland Museum, brought back memories of that journey. On that gray day in Portland, two works in the collection stood out.

Winslow Homer (1836-1910)

Winslow Homer (1836-1910)Sharpshooter, 1863

oil on canvas

12 1/4 x 16 1/2"

Portland Museum of Art, Maine

USMC Sniper Team, 2004

USMC Sniper Team, 2004Photo by: Gunnery Sgt. Keith A. Milks

Winslow Homer's "Sharpshooter" is as relevant as the front page of today's New York Times.*

Alexander Eliot in "Three Hundred Years of American Painting" describes how Winslow Homer's "huntsman eyes saw the world his contemporaries saw, only much more sharply." For Alexander Eliot, Homer's paintings are "products of intense and reverant looking, carried on for, not for hours or days, but for years."

Hiram Powers (1805-1873)

Hiram Powers (1805-1873)Bust of "The Greek Slave", after 1845

marble

24 1/4"

Portland Museum of Art, Maine

Hiram Powers artwork,"The Greek Slave", was arguably the most famous contemporary sculpture in mid-nineteenth century America. The bust in the Portland Museum is derived from the full figure sculpture that toured the United States.

Over one hundred thousand people paid to see "The Greek Slave" during its 1847-1848 tour.

Over one hundred thousand people paid to see "The Greek Slave" during its 1847-1848 tour. Robert Hughes in "American Visions" explains that an American artist could approach the concept of the Ideal "if he lived in Italy, and between 1830 and 1875 about two hundred of them did. Notable among them were the 'American Florentines,' led by a former machinist from Cincinnati, the sculptor Hiram Powers."

Hughes goes on to explain that Power's "Greek Slave" was a modern retelling of the Uffizi's "Medici Venus" with chains added as a cache-sexe: "This, Americans thought was the first truly moral nude they had ever seen."

What I enjoy most about the Portland Museum's bust of the "Greek Slave" is the absence of chains and the anecdotal context that shrouded Power's full scale version. We can look upon this work as a sculpture of a real, though idealized, woman. As viewers, we are not told what to feel nor does her nakedness seem unwilling. Without bound wrists, the overt moral clothing that covered her is absent. The figure is more ambiguous and more modern.

* (As I write this the 2,000th US death in Iraq has been announced)

Comments